Why Your Nervous System Needs Therapy, Part 2

When you think about counseling, I bet you don’t immediately think about your nervous system. It’s probably pretty low on your priority list of things to discuss with your provider, and yet, it’s such a central part of our functioning that it deserves some attention and care. This is part two of a 3-part series about how our nervous system can hijack our mental health and what we can do to help.

Disclaimer: I am a mental health counselor, not a biologist, medical doctor or neurologist — my understanding of nervous systems comes from this perspective and knowledge, this is mental health/emotional health advice, not medical!

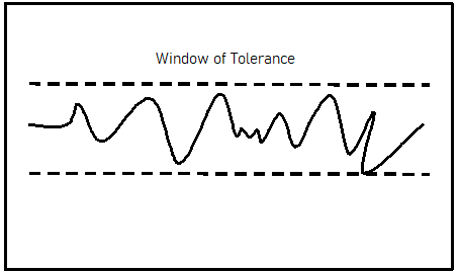

When we talk about our mental health through the lens of our nervous system, it’s important to consider our window of tolerance. Our window of tolerance is the amount of unpleasantness our nervous system can handle before the sympathetic nervous system kicks on and pushes us into fight/flight/freeze. It is a largely stable window – it doesn’t change from day to day and each of us has a different size window. With time and practice, we can widen our windows. Within our window of tolerance, we are able to experience a full range of human emotion including anger, sadness, hope, joy, fear, etc. Outside our window of tolerance, our downstairs brain takes over and we do what we can to just survive.

Most of the time, we may feel like we’re moving around within our window and we’re doing okay. The various ups and downs of life feel manageable, we can respond to them, roll with the punches, go with the flow, etc. If you’re able to connect with yourself in those moments and answer yes to these questions, “am I mostly attune to myself and the world around me? Can I hear and satisfy my needs in this moment to some degree? Do I feel somewhat confident and capable that I can do this?” you’re likely in your window.

Sometimes, however, we have an experience that kicks us outside of our window. The kids are fighting you on virtual learning, your boss is unhappy with productivity, your friend said something incredibly invalidating and to top it all off your spouse is asking for more of your time and attention?! The fire starts building inside and our downstairs brain kicks on and tells us: Fight! Run away! Now! Do something! Protect Yourself! In essence, “run from the tiger!” When you’re being chased by a tiger, you’re not likely to reflect on the validity of said tiger, the probability of harm caused by the tiger or the six-step acronym your therapist has been teaching you to respond to the tiger. You’re just going to run.

Other times, you may be bombarded with thing after thing, and it feels like you’re getting buried alive by all the stress and weight of the world. At this point, your brain doesn’t seem to be working, you’re foggy, fatigued, forgetful, maybe you find yourself zoning out, “checking out,” rereading the same line of work again and again but not taking it in. Maybe you finally get a chance to sit on the couch and realize that 2 hours have passed and you’re not sure where your mind was. Your downstairs brain has become so overloaded that it’s realized (in its mind) that to survive it needs to conserve energy, slow down, turn things off and, yep, you guessed it: Freeze.

Sometimes, we bounce from one side to the other, completely bypassing the window of tolerance. Here’s a completely hypothetical scenario: You’re in a global pandemic that has forced you, your partner and your two children to work and learn from home alongside your brand new puppy you got for Christmas 2019 thinking it would be “the right time.” Your internet is too slow, your children hate learning online and the more they miss their friends, the more they seem to hurt one another. Your partner and you have no space. You have no time to yourself since no one leaves the house anymore and you just want some serious peace and quiet. But there’s no end in sight so after a particularly tough day, when your mom calls to complain to you about something, you snap. You yell at her, you kick the dog outside who peed on the carpet for the 4th time this week, you throw dishes around in the sink and send the children to bed seething with how much people seem to need from you. The Fight response is strong, y’all. Let’s imagine you have a punching bag in your garage; you’d probably beat the sand out of it — can you feel the fury building up and the felt sense of release when you imagine that explosion of energy? Oh, but then the shame kicks in. Collapse on the floor, crying, folded over feeling completely empty and shut down – you have no more energy for any of it anymore. Freeze. Maybe your partner approaches and says, “honey, I can’t find the [insert literally anything]. Did you forget to buy it at the store?” Fight. (Or Flight, either one is plausible here.)

See how there’s not a single second to catch your breath and regulate in the midst of all of it. It’s no wonder we’re all running on empty – the sympathetic nervous system, that’s meant to only pop on when it’s needed and then turn off as soon as it’s not needed again, has been running on high alert for a really long time.. Too long. We have no energy left to regulate.

When we’re outside of our window of tolerance, our upstairs brain doesn’t work so well. We tend to operate based on instinct: what’s going to be most helpful the fastest to get me through this? Can you see how alcohol might help here (flight)? Or punching someone in the face (fight)? Or an entire day of nothing but video games or Netflix (freeze)? This is why the skills your therapist may keep teaching or the things you’re reading in the books isn’t helping: because it’s not so familiar to you that you can do it without thinking.

The skills we use to regulate need to become familiar, instinctual (see the full circle we’re doing here!). Otherwise we’re never going to be able to use our upstairs brains to support the downstairs. Next week, we’ll look at some skills that can help bring us back into the window of tolerance.